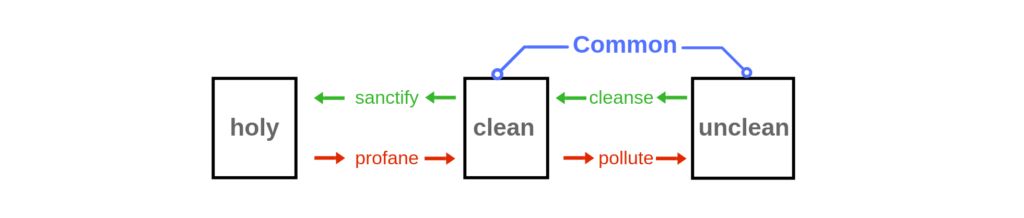

Chapter 11 begins a new section in the book of Leviticus, one that deals with the various kinds of uncleanness and what is to be done to make someone clean again. This follows from the discussion Yahweh had with Aaron in chapter, which is that there are to be distinctions between what is common and what is holy, what is clean and what is unclean. How can they know the difference? The Lord will tell them.

It’s important to remember here that these instructions are coming within the context of a narrative, they aren’t just a legal recording of laws. Thus, the story frames the laws, not the other way around. If we take it out of that context it can easily look as though these instructions apply to all people at all times. However, they are directed to these specific people at this specific time. They are part of blueprint for what makes the nation of Israel holy. But as the New Testament makes clear, they are not applicable forever and never were for Gentiles. That said, they are not without value. We can still profit from knowing the intentions of these laws and what they were supposed to achieve, as well as why they were eliminated under the new covenant brought about by Jesus.

Chapter 11 specifically focuses on animals. They are further classified by land, water and flying creatures with a listing for each on those that are edible and those which are unclean (these are the same classifications of animals found from Genesis chapter 1). For land animals, where they have divided and cloven hoofs and chew the cud are clean and can be eaten. Any land animal where both of those things aren’t true is unclean. Just in case there was any confusion at this, the Lord provides a few examples of animals that only meet half the criteria with the reinforcement that they are unclean (the camel, the coney, the pig, etc.). By the way, many of the Hebrew terms for these animals are unknown, scholars are only firm on 40% of them. So, don’t be surprised to find variations in translations on the animal names.

Given the examples, by the way, it should be clear that the English phrase “chew the cud” doesn’t quite get at what is being described here. We think of cud chewing as chewing of the plant, storage in the stomach, regurgitation at the leisure of the beast, and then a more thorough mastication. Although this is true for cows, it’s not true for camels, who are described as those who chew the cud. Probably best to understand this as meaning animals who chew their food thoroughly.

Immediately, we want the questioned answered, what makes animals that don’t have both divided hoofs and cud-chewing tendencies unclean? We’ll get there but it may make sense to look at the other examples before trying to understand why these distinctions are what they are. For water creatures, only fish with fins and scales that live in the water can be eaten. If they live in the water and don’t have fins and scales, they are detestable (unclean).

For flying creatures, we have a list of birds that are unclean (they seem to be primarily birds of prey). Then we are told flying insects (that walk on all fours but have wings) are inedible but hopping insects are ok. Other animals that swarm (the Hebrew word for swarm has the connotation of creeping, crawling, wriggling) are also unclean (think lizards and mice the like).

Then we get a list of the pollution of these unclean creatures and how to become clean. For land animals, those who touch the carcass of an unclean animal will remain unclean until evening. If you carry the carcass, you have to wash your clothes, too (this is true for animals that are clean as well as we see in v. 39 and 40). Same thing with swarming creatures. If any animal dies and falls onto something, it’s unclean until evening as well (including wood, sacks, clothing, other work-type items). It also has to be placed in water (washed). However, if something unclean dies into a pot, it’s unclean for good and must be broken. If water was poured out from the pot while the unclean creature was in there dead, it is unclean (the assumption is that it cannot be eaten/drunk because you can never eat an unclean animal). However, wells, springs and cisterns are not unclean if the animal dies in there, just the animal and whoever has to fish it out of there. Unclean animals can fall on seeds, no worries. But if it’s watered and then the unclean beast deceases upon it, it’s unclean.

It’s worth noting that the uncleanness of certain animals is not as serious as some of the uncleanness that is to come in subsequent chapters. It also isn’t particularly unnatural to become unclean, sometimes you just have to move the carcass of an animal you were going to eat. Generally, uncleanness related to animals at the most constitute waiting until evening and washing yourself and perhaps your clothes.

The chapter ends with a context from God as to why He is making distinctions here. “For I am the Lord your God, and you must sanctify yourselves and be holy because I am holy. […] For I am the Lord your God who brought you up out of the land of Egypt to be your God; you must therefore be holy, for I am holy.” If they are going to be His people, they must be holy , set apart, distinct from that which they are surrounded by. This is not just an issue of identity, it’s an issue of purpose. Remember, they are a “…kingdom of priests, a holy nation…”. They serve a mighty God who brought them out of Egypt and they must show themselves distinct in the world just like their God is distinct.

So broadly, these laws are relatively straightforward, there are only handful of criteria in determining what is clean vs. unclean and the solution to uncleanness related to animals is pretty consistent across situations. The rationale for the distinctions themselves, however, has been a subject of discussion since before Jesus’ time. Why can they eat cows and sheep but not camels or pigs? Why are mice, owls and eels unclean but grasshoppers not? There are four primary explanations for these distinctions and they are: arbitrary, cultic, hygienic, or symbolic.

Option 1 is that the laws are arbitrary, meaning there is no consistent reason across the distinctions, they are simply things that God has chosen because it His prerogative to do so. Perhaps we are drawn to this as it allows us to stop asking the question and move on, but is both potentially lazy and runs the risk of being unprofitable if we are missing potentially deeper distinctions. It’s a viable option, but it’s best we evaluate the other options before landing here.

Option 2 is that the laws are cultic, meaning they were chosen to make distinctions between Israel and the worship practices (and deities) of other cultures. This seems like a reasonable explanation, especially given the context provided at the end of the chapter that Israel was to be holy like God is holy. One would suppose that would mean they can’t be engaging with animals that were knowingly associated with the worship practices of other gods. This thought was also shared by Origen, the 2nd century church father, historian and theologian. He believed that certain animals were associated with certain demons (false gods whom accepted their affiliated animals as sacrifices) and notably, that, “…a wolf or a fox is never mentioned for a good purpose.” (http://www.newadvent.org/fathers/04164.htm, chapter 93). He has tied this to Egypt specifically, who have gods in the likeness of wolves, foxes, eagles, owls, etc.

However, although we can find situations where this option makes sense, it hardly explains it holistically. The Canaanites, for example, sacrificed the same range of animals as Israel did yet they are not declared unclean. Specifically, the bull was a primary pagan worship animal in both the Egyptian and Canaanite rituals but was allowed for sacrifice to Yahweh. So, unfortunately, although this option is appealing, it only makes sense in limited circumstances.

Option 3 is that the laws are hygienic distinctions, meaning that certain animals are declared unclean because they carry disease. The broad thought would be that the clean animals are safe to eat while pork can be a source of roundworms, the hare carries tularemia (bacteria that often can kill tons of rabbits of mice when it breaks out), and fish without fins and scales tend to burrow in the mud and become sources of dangerous bacteria. Similar risks exist for birds of prey who eat raw meat. You get the idea.

However, this option suffers from the same issue as option 2 in that it only makes sense for some of the prohibitions. We may recognize today that cows aren’t immune to disease, “mad cow” disease comes to mind. And in that day Arabs considered camel flesh as a luxury where Israel was to treat it as unclean. Further, it isn’t like Israel didn’t cook animal meat, they were to thoroughly drain blood and cook things to avoid consuming blood of animals anyway. In which case, some of the risks of the unclean animals causing sickness would be mitigated. Additionally, we don’t get any sense of this distinction in the text. If true, it would also be practical, and it seems like a reasonable thing to have called out that they needn’t worry about some of it if they just cook the meat.

Additionally, poisonous plants are not declared unclean. For their own protection, this seems like it would have been a worthy call out. Finally, if health was the underlying reason for the distinction, it makes little sense that Jesus would ultimately proclaim those same foods clean. If the nature of the pig is that it is filthy and carries disease, the proclamation to Peter to “kill and eat” the meat on the sheet in Acts 10 was a command to potentially poison himself. Overall, although it’s not impossible that there are instances of some unclean animals also being those who carry disease and thus creatures they shouldn’t eat anyway, the hygienic option remains unsatisfactory, just like the cultic option and for the same reasons.

Option 4 is that the distinctions are symbolic, meaning that the food laws point to the behavior and habits of clean animals as living illustrations on how Israel should behave while the unclean animals are illustrations of sinful men. This is a rather ancient explanation, going back to pre-Jesus Jewish writers and something that more folks are latching on to today as a possibility. As an example, this option might look at the animals that chew carefully that which they are to digest as being an example to humanity to carefully meditate on the words of God before taking them in. They may also look at the pig and recognize it wallowing itself in the mud (sin) and enjoying it, where as the sheep is a clean animal who reminded Israel that the Lord is their shepherd (many moons before Psalm would say it, we may add).

This is an interesting option but also one that is difficult to nail down. It is undeniable that Scripture is saturated in symbolism. Those who reject that do so in fear of the vast array of interpretations of such symbols under the thought that God would not produce something that can potentially be so misconstrued. Their rejection of symbolism as a whole is inappropriate but their caution is well heeded. In this instance, if one were trying to find examples to demonstrate each and every one of these laws as a symbol of human behavior, I’m certain you could find one to be satisfied with. But the fact that you could stretch a symbol to fit doesn’t mean it’s actually true. For example, I’m not sure the first reaction of the average fella to see a cow chewing the cud is to be reminded of patient and ponderous intake of the Lord’s word. Maybe it’s just me.

There is an Option 5 for consideration that is primarily symbolic but is far less subjective. The core distinction here is the notion of cleanness being akin to “purity” or even “normal”, something wholly of what it is intended to be. Humans are clean when they are as they should be, unstained by sin and untouched and unimpacted by anything that is unclean around them. Dead animals are unclean, regardless of any other categorization, because they are dead and are intended to be alive, that is their “normal” state.

We see this in other ways as well. Priests, for example, were to be free of physical deformity (to have a deformity was to not be wholly what it was intended to be). As we look at the laws of this chapter, we can see the distinctions in the categorizations of the animals, specifically in their mode of motion. They are separated into animals that fly in the air, those that walk on the land and those that swim in the seas. To swim in the seas, fish have fins and scales; to run on the land, animals have hoofs, to fly in the air the birds have two wings and another two for walking. The animals that conform to the “normal” use are clean. Those who do not are unclean. Fish without scales are unclean. Insects which are intended to fly but who instead walk are unclean. Animals who don’t have a distinct motion (the swarming creepers) are unclean. This starts to make sense but doesn’t speak to differences between, say, pigs and sheep. This may come from the nature of the community as farmers and their familiarity with sheep and cattle. To the extent those are the “normal” animals they interact with that they consider clean, animals that don’t match their behavior exist outside the boundaries of clean animals.

We also notice, in the land animals and air creatures specifically, a further distinction that is between those that are unclean, those who are clean, and those who can be sacrificed. This parallels the divisions in mankind between the unclean (those excluded from the camp), the clean (majority of Israelites), and the sacrificial (the priests). This symbolism is interesting in that we see man and beast coupled in a number of different ways being treated or thought of similarly (for example, the blessings in Genesis and the dedication of the first born in Exodus 13). If we think this symbolism of animals to humans makes sense, the restrictions on the birds of prey also makes sense. They are detestable because they eat things from which the blood has not been properly drained.

Grand narrative on option 5, then, is that the laws expressed an understanding of God’s holiness and pointed to Israel’s special status as the holy people of God. The division into the edible and inedible foods symbolized the distinction between Israel and everyone else (Gentiles). Israel, as God’s chosen, were in their “normal” state in right relationship with God so were pure, just like the examples in the clean/unclean animals. Every meal and every sacrifice reminded them of God’s restricted choice of this nation among all the others, of His grace towards them in this matter. It also reminded them of their responsibility to be a holy nation. In that, they were reminded that holiness was more than just what they ate, it was a way of life characterized by purity and integrity.

Is this a reasonable option? Arguments for it include its comprehensiveness; it does not suffer from some of the issues of only fitting certain situations like the previous options. We also see this symbolism between humans and animals related to the law show up in other writings and explanations of these laws in antiquity. Further, the New Testament does see the food laws as a symbolic division between Jew and Gentile and Jesus declares all foods clean as a consequence of all, Jew and Gentile, being united by Him in this new agreement or covenant. As the distinction between Jew and Gentile became obsolete, so did the food laws that served as a reminder of that distinction.

What do we do with them today? We can recognize that these laws point to a holy and pure God who still calls us to be holy and pure like Him. We remain a “chosen race, a royal priesthood, a holy nation, God’s own people” (1 Peter). We run the risk, perhaps, that these laws were meant to curb in the ancient Israelites, and that is the tendency to forget God’s holiness, His call on our lives to live consistent with that, and a constant reminder of His gracious actions towards us, His unwarranted mercy and His granting to us the honor of bearing His name when we do not deserve it.