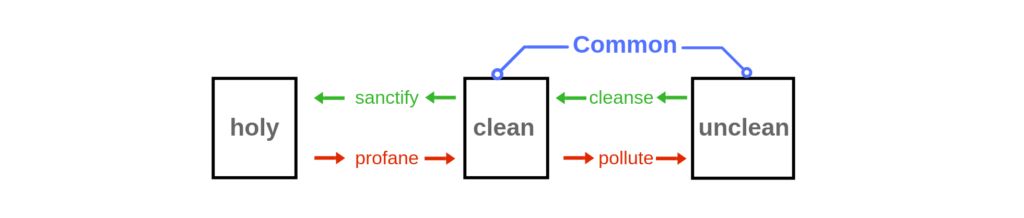

As we move into chapter 5, it’s probably appropriate to try and make distinctions, where possible, among the sacrifices over the last few chapters and into this one. Although often called the “sin” offering (a reasonable translation but perhaps not exactly the concept as we normally think of it), chapter 4 should be more appropriately referred to as the purification offering. The whole point is purify the tabernacle so they can even enter to be able to offer the burnt offering that is actually for atonement. The presence of sin defiles God’s sanctuary so it must be purified. sin doesn’t happen in a vacuum, it pollutes things around it. So this offering addresses that. God is not endangered by this pollution of course, but man certainly is. We know when unclean and holy attempt to occupy the same space, holy wins and unclean is destroyed.

So chapter 5 continues addressing situations where common folks require the purification offering. Note that the lay folk don’t bring as valuable an offering compared to the priest (a nanny-goat or lamb vs. a bull, or even pigeons, turtledoves or flour if they’re poor). Particularly, the examples are sins of omission, times when you are supposed to do something but intentionally choose not to. Broad point is that things that are sinful or that make people unclean are applicable in fact, even if we are unaware of them. You can be unclean and not know it or have committed a sin and not realized it (basically the opposite of walking into it willfully). Either way, it’s still true and still has impacts. And, as soon as you are made aware of it, regardless of how, it must be addressed. (Our tendency may be to figure that since it’s been some time and is separated from the event, it can just be ignored. That would be a mistake. As noted before, sin has consequences and impacts beyond the event itself.)

Then the discussion switches to discussing the guilt or reparation offering (reparation is probably a more appropriate way to talk about it as the core focus is on addressing those additional consequences of sin, more specifically violating God’s holiness. The examples include trespassing on God’s holy stuff (could be eating holy food, touching stuff dedicated for the priests, etc.) but done unintentionally. Once it’s realized, the reparation sacrifice must be made and a restitution must be made to make up for what was defiled.

The next example seems mostly the same although this one is likely pointed to someone who doesn’t know exactly what he defiled, he just feels a guilt. Basically, someone believes they have sinned against sacred property but aren’t sure how. So, they make the reparation offering, but there is no extra fifth to tack on for this one because he doesn’t know exactly what he infringed on. Although it moves into chapter 6, the first few verses that follow are of similar concept, someone infringes upon God’s holiness by swearing falsely (lying and using God’s name to seal the deal). The reparation offering must be made (in addition to the purification offering, to allow access to make the burnt offering for the sin itself).

So, up to this point, we have various sacrifices of offerings that describe the effects of sin and how to remedy it. The burnt offering focuses on the individual, a sinner who deserves to die and an animal dying in his place. God accepts the animal as ransom or covering for man. The purification offering uses a medical view, sin makes the world dirty so that God can no longer dwell in it (it’s unclean). The blood of the animal cleanses the sanctuary so God can still be present with his people. And the reparation offering sees sin as a debt that man incurs against God. The debt is paid through the offered animal.