God had laid out how to ordain the priests for service back in Exodus 29. Here, Moses executes on those instructions. The Lord tells Moses to grab Aaron and his sons along with some animals to sacrifice and the special clothes that were created for the priests and head to the tent of meeting, that’s where it will all go down. In addition, the congregation is to be gathered to witness all of this (this isn’t everyone, they all wouldn’t fit, most likely the elders of the people are here representing everyone).

First, Moses washes the fellas. This is something the priests were to do prior to starting priestly service, but they weren’t priests yet, so Moses does it for them. This will persist, things that the priests will be responsible for Moses will handle as part of their initiation. Then Aaron is dressed in all the action, the shirt, the cloak, the sash, and that sweet breastplate with the gems representing the 12 tribes and a spot for the Urim and Thummim (those items used to determine the will of the Lord). We don’t think much of uniforms, they seem stuffy. But it’s not about the person, it’s about the position. You could pick the High Priest out by the sweet gear he had on, and it was a reminder of the who he’s in service of (Yahweh, of course), the important work he did (securing atonement for the nation) and the role of each individual to be part of the “kingdom of priests”, the calling of God’s people from Exodus 19.

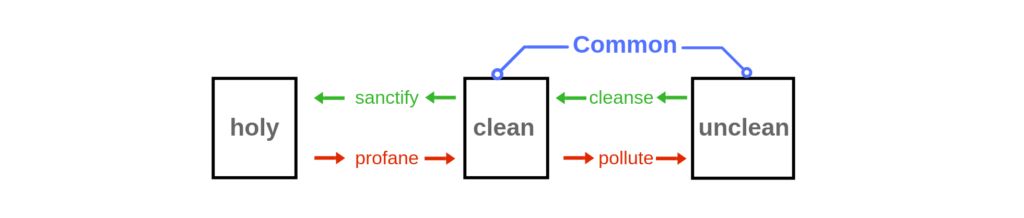

Then Moses breaks out the oil, instructions from Exodus 40, and uses it to consecrate the tabernacle, the altar and Aaron and his boys. They are being identified for God’s service. That’s followed by the sin (or purification) offering. This isn’t for the the fellas themselves, it’s for the tabernacle, it had to be purged from sin’s pollution, specifically those introduced by the priests themselves. The blood is smeared on the altar to purify it (necessary, as this will be followed up by the actual burnt offering which needs a purified altar, otherwise it will be tainted).

The ram is sacrificed for the burnt offering, this is for their personal sins. The burnt offering allows them to reconcile with God by offering up a ram in their place as a ransom for their sins. Then there’s the ram of ordination. The blood of the animal is touched to Aaron’s right ear, right thumb, and right toe. This is a merism, parts that represent the whole. What’s the purpose? Likely a few things. This identifies the role of the priesthood explicitly with sacrifice. Also, it could be a kind of peace/confession offering, where Aaron is confessing God’s mercy for choosing him as high priest.

Finally, they are to stay in the tabernacle for 7 days, repeating the burnt offering every day. Although it only takes a moment to defile yourself, the sanctification of that is generally a slower process. We see similar instructions of avoiding normal social contact when demonstrating cleansing from disease and upon life events that caused someone to become unclean. They are to keep the instructions of the Lord under penalty of death.

Broad takeaway in this chapter is the reminder of the pervasiveness of sin, even for those chosen to be in the highest service of the Lord. These men who are in service to God brought pollution in with them so a sacrifice had to be done to cleanse the place so the burnt offering for their own personal atonement could be made. Even their skin and clothes have to be sprinkled and purified. And the sacrifices must be done more than once because sin is deep-rooted and often recurs. In the light of Jesus, our need for daily forgiveness does not go away. However, the blood of Jesus cleanses us from all sin, rendering the sacrifices and ritual we find in Leviticus no longer necessary.